Frackalachia.

The realities of the natural gas economy in Appalachia, according to Sean O'Leary of the Ohio River Valley Institute.

The Cocklebur interviewed the Ohio River Valley Institute’s (ORVI) Sean O’Leary on his research about the broken promises of job creation and local economic benefits from the natural gas boom in Appalachia. I recommend reading O’Leary’s “Frackalachia Update: Peak Natural Gas and the Economic Implications for Appalachia” and “Fracking Counties Economic Impact Report—Natural Gas Counties' Economies Suffered as Production Boomed.”

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Cocklebur: We know that fracking and natural gas has hit the national spotlight once again, becoming a pretty major campaign issue within both parties for different reasons. I was hoping you could paint the picture on the ground in Appalachia. What is the reality of the situation for fracking in Appalachia, particularly in the battleground state of Pennsylvania. What's going on with the jobs picture? What are you seeing on the ground in terms of the promises versus the reality?

Sean O’Leary: If you take a look at a couple of our reports, it's pretty much as you would expect. If you go back to 2008 and 2009, there was widespread expectation at the time that the coming natural gas boom was going to be an economic game changer. When I say an economic game changer, I remember sitting down with John Doyle, who was at that time probably the most progressive member in the West Virginia House of Delegates. And I can remember Doyle saying to me that we're going to have more jobs than we have unemployed people. I mean, he genuinely believed it. Doyle was the most environmentally attuned, most progressive guy in the entire legislature at the time, and even he genuinely believed in the natural gas industry and their economic impact reports, that I’ll note were prepared and commissioned by the American Petroleum Institute.

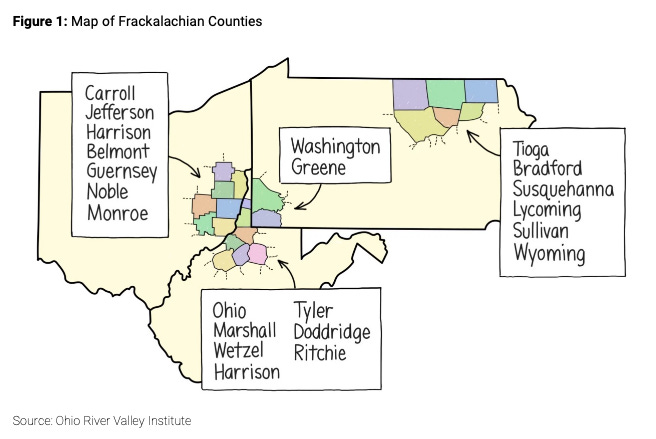

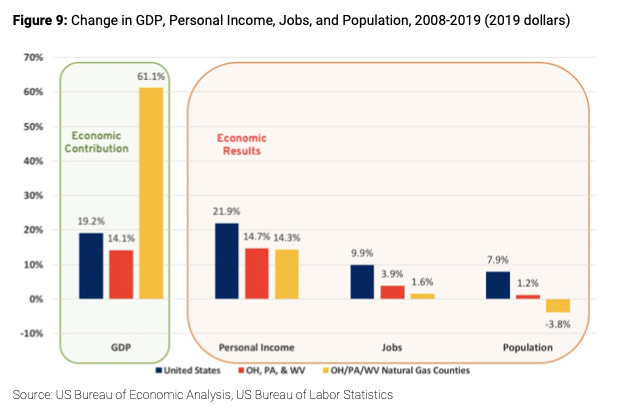

The industry expected that between 40 and 50,000 jobs would be created in West Virginia. In Pennsylvania, the number was north of 200,000. The was long before ORVI had been formed and I was running a marketing analytics company. I was very deeply skeptical about all of those promised jobs and I wrote a number of op-eds explaining why it wasn't going to happen. Jumping to the present day, the natural gas boom did take place in Appalachia and those 22 counties that I had mentioned went from being a non-entity with respect to natural gas production, to becoming the highest producing region in the United States and one of the largest in the world. We're talking about a 15 year window going from zero to 600 miles per hour. In conjunction with that boom, gross domestic product (GDP), many people's go-to measure for economic prosperity, went absolutely through the ceiling.

The Cocklebur: That was one of the shocking findings in your reports. GDP just skyrocketed but jobs did not. What happened to all of the jobs?

Sean O’Leary: None of the measures of local economic prosperity, like jobs and income and population, none of them moved. Or to the degree that they did move, they actually went into decline. In those 22 Appalachian counties combined, there are 10,000 fewer jobs now then there were at the time the fracking boom began. The population in the region is down by almost 50,000 people, and that's out of a region that had just under a million people to begin with. So it's about a 5% population loss

The Cocklebur: So that huge GDP that's being generated then, that means a lot of money is changing hands. But where is all that money going?

Sean O’Leary: We actually have a pretty good handle on that. To throw in one other little bit of context, the other claim that the industry makes very frequently to impress people with their significance is the amount of money invested. For a reference point, Cleveland State University regularly tracks industry investment going back to 2010. And so far they've counted, in Ohio alone, more than $100 billion of investment. When you ask, where does all the money go? There are actually two really big buckets of money. One big bucket of money is the revenue that's generated from the sales of all of that gas. But the other bucket of money between Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, we’re probably over $300 billion in industry investment at this point. That’s building structures, seeking new sources, building and syncing drill pads.

Within the industry, when it comes to investment and revenue, somewhere between 7% and 8% is all that goes to labor. The rest of the money goes to capital, which is just a broadly defined category of the companies, the management, the shareholders, the banks who loan the money to finance all of this development. In other words, very, very, very little of the money actually lands in local economies,

There are only three ways in which money can even theoretically show up locally. One is in the form of employment, in the form of jobs. Another one is in the form of royalties. The companies pay to access gas on private land. The third one is taxes, severance taxes and other taxes that the companies pay. The problem that we have is that relatively little of the money goes to support jobs because there aren't that many jobs to begin with. And because the industry doesn't have a long heritage in this region, many of the jobs that were created went to companies and contractors from out of state. Lots of white pickup trucks with Oklahoma and Texas and Louisiana license plates running around the region. So that was vastly disappointing.

The royalty revenues that might have kicked into local economies has been greatly diluted by around 90% largely for two reasons. Number one is we're a region in which a lot of out of state interests have immense land holdings. In West Virginia, for instance, it's been estimated that 75% of the real estate in the state is owned by out of state entities. That’s derived from West Virginia's coal mining and lumber industry heritage.

The second part is that there’s only a relatively small number of people who get significant royalties from the industry, and some of them did get rich. I mean, it's not that no one has benefited financially from the boom. The caveat to that is that when most people get large infusions of cash or income, you realize what most people do with that kind of money. Typically, what they do is they pay down debts, invest in retirements, fix up their house, buy a second home at Myrtle Beach.

Finally you have taxes, West Virginia is largely the exception in this, but Ohio and Pennsylvania have gone out of their way to try to encourage industry development in various ways. Either not imposing taxes like severance taxes or reducing company tax liabilities, whether it's for personal property or mineral property. So, even though there are increased tax revenues that come from the industry, they're not remotely in proportion to the amount of economic activity that's taking place. Even those benefits are limited which means very little money actually stays in local economies.

The Cocklebur: Do we know anything about local people in the Appalachians think about the industry. You said there are about a million people region. What do they think about the frack gas industry? Is it popular? Do the people want more regulations or protections, or are they happy with the status quo? I know you’ve done some public opinion polling on this issue.

Sean O’Leary: It’s important to note that folks in the region are still inundated with messages from various policy makers--and certainly from the industry itself—that gas is vital to economic development in the region. That’s particularly true, by the way, in Pennsylvania where Josh Shapiro, the Democratic Governor, has since leaving his previous job as Attorney General to became Governor, he's been very, very supportive of the industry. He speaks frequently about its economic importance even though the numbers don't back that up. As a result of being inundated with that kind of a narrative on the one hand, but also faced with the reality of walking out your front door and looking up and down the street, I think at best people are very ambivalent about it and certainly very disappointed.

It’s very similar to parts of West Virginia where the coal industry is both a blessing and the curse. I mean, it might be killing you in a number of ways, but if it's the only game in town you kind of cling to it. It's almost a Stockholm Syndrome type effect. I think people are generally pretty divided about the industry at this point. They hate what it is doing from a pollution and health standpoint, but on the other hand the region has suffered immensely economically going back to the 1980s when the steel industry collapsed, in particular. They know there's no jobs boom going on. I spend a lot of time working with county commissioners and folks like that, who in many cases were very supportive of the industry at first and believed in it. But at this point they know all of those jobs never appeared and the industry’s economic benefits never arrived.

It’s a very muddled picture. I have listened to the Harris campaign and certainly the Biden administration before it, and I think that they must imagine that support for fracking is much more categorical than I certainly think it is.

The Cocklebur: You mentioned the Biden Harris Administration. Is there anything happening on the ground in that region from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law or the Inflation Reduction Act. Are local people accessing any of those funds for cleaning up abandoned wells or doing restoration work?

Sean O’Leary: Yes and no. It's partly because the footprints of the coal industry and the natural gas industry overlapped to some degree but not entirely. A lot of the abandoned mine and well money is starting to flow and we're really thrilled that it's happening. But most of that money is focused more on the coal counties in central Appalachia, the southern coal fields of West Virginia, Eastern Kentucky. They're seeing more money there than we are in more northern Appalachia. We’ve seen some development related to the Inflation Reduction Act. There's a long duration battery plant in Weirton, West Virginia, and some other local projects. Probably the federally-funded effort that has certainly gotten the most attention in the press in the region is the selection of Arch2 as one of the seven regional hydrogen hubs around the country.

From the ORVI standpoint, this is a very problematic issue because when you talk about hydrogen in this region, you're talking about blue hydrogen hydrogen that's made from methane natural gas. That takes us back to fracking and then we're back to the question why would we went to do that?

The Cocklebur: There seems to be a lot of political support for exporting natural gas, and also a lot more broad support for climate action. What do you see as the future for the industry?

Sean O’Leary: Our anticipation right now is that the natural gas industry in Appalachia has probably peaked in terms of its output. With the industry peaking, whatever hopes that anybody ever had for economic development on the back of this industry are probably now dead. The industry has basically reached full maturity, and is probably going into some degree of decline. For the last three or four years, virtually all of the growth that you've seen in natural gas production has come out of the Permian Basin and in the Hainesville regions that are closer to the Gulf Coast.

The biggest need in the region, and it has been the case for a long time, is that if you care about economic development and local prosperity, you’ve got to turn away from the gas industry in particular and begin to focus on other economic sectors. Gas has never has been an engine for local economic prosperity since it scaled up in 2008. There are new export terminals being built, but we're seeing great reductions in natural gas consumption in Europe. California is reducing natural gas use. Texas is an interesting case because they just threw something like $5 billion to see the creation of a bunch of new gas fired power plants there. It was basically an act of desperation because for the last two-to-three years, there hasn't been any growth in gas fired power production in the United States.

The Cocklebur covers rural policy and politics from a progressive point-of-view. Our work focuses on a tangled rural political reality of dishonest debate, economic and racial disparities, corporate power over our democracy, and disinformation peddled by conservative media outlets. We aim to use facts, data, and science to inform our point-of-view. We wear our complicated love/WTF relationship with rural America on our sleeve.