Monopoly Farmers and the Farm Bill.

A handful of the largest agricultural producers aligned with corporate agribusiness have outsized influence on federal farm policy. Will they get their way in this Farm Bill debate?

This analysis was co-written by Jake Davis.

Long overdue federal Farm Bill negotiations will finally being in earnest this week as the House Agriculture Committee will meet May 23rd to mark-up Chair Glenn Thompson’s (R-PA) draft bill. Congress has convened numerous hearings and panel discussions soliciting Farm Bill input over the last few years, but the bill draft release followed by committee mark-up is the first substantive legislative movement.

With specific details in text, more media paying attention, advocates generating pro-and-con statements, and members of Congress issuing official statements, the Farm Bill debate momentum is here. The current bill expires on September 30th, 2024.

The Farm Bill negotiation process will continue throughout this election year. Decisions made by legislators through the markup and amendment process in the Agriculture committees and on the full floor of the House and Senate will determine who benefits most from the Farm Bill for the next five years.

Political and policy divisions have already emerged on large budget pricetags like nutrition benefits and raising reference prices to benefit a very small number of wealthy rowcrop producers. The Senate Agriculture Committee, led by Democrats, has yet to release its full draft. The House Agriculture Democrats did release a list of responses rejecting the Thompson draft earlier this week. The responses include a laundry list of organizations opposed to the Republican draft, primarily groups that fight hunger and poverty, advocate for conservation and science, and support local food and sustainable agriculture.

Suppose Republicans on the House Agriculture Committee get their way. In that case, a very small group of farmers who enjoy payments from commodity crop subsidies, have massive government-supported industrial livestock operations, and reap the lion's share of risk elimination from crop insurance. In short, what we like to call “Monopoly Farmers” will be the winners of the process. At the same time, the tens of millions of people who benefit from nutrition spending will face increased hunger, increased poverty, and more reliance on the already struggling emergency food distribution system.

Big Ag Cashing in on Farm Bills since 1996.

The path to the current farm policy began a generation ago. When Congress passed the 1996 Farm Bill—the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996—proponents of the “get big or get out” school of agriculture and farm policy celebrated. They had finally squashed the last vestige of New Deal farm programs. Dubbed “Freedom to Farm” by its supporters, most family farm groups at the time rightly predicted a collapse in the number of farmers and farm income, as well as increased concentration of market power by a handful of agribusinesses and massive farms. Those family farm groups were right.

As the Missouri Rural Crisis Center’s Rhonda Perry explained, “In 1996, we got a new farm bill that was hailed as the ‘Freedom to Farm,’ which is now being called ‘Freedom to Fail.’ We got the best farm policy corporate money could buy. Cargill, ADM, and other multinational grain traders wrote this farm bill and made sure it got implemented with no public debate.”

With these disastrous outcomes, we prefer the term “Wall Street Farm Bill” to Freedom to Farm. Our colleague Austin Frerick coined the term in his groundbreaking book: Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America's Food Industry. (UNPAID PLUG—pick up your copy of Austin’s book from Island Press or your local bookstore today if you don’t already have a copy. Cocklebur readers will love it!).

Monopoly Farmers.

The Wall Street Farm Bill did it’s job, eliminating government intervention in the marketplace and assuring fencerow-to-fencerow farming. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, farmers overproduced subsidized grains and livestock that consume cheap grain, causing a historic economic crisis in farm country. Most farmers, rightly, blamed the meatpackers and grain companies for their ills. Many farmers participated in efforts to break up agriculture monopolies, make markets more fair, and increase competition through a variety policy measures.

What is often left out of the conversation, however, is a critique of the system that promoted land and wealth accumulation by some farmers while leaving many others in the dust (or in deep debt). Some farmers, the largest farmers--those with deep pockets or good credit, those who inherited the most productive land in the country, those with sweetheart contracts from meatpackers and grain processors and ethanol plants, those with vast government support through payments and insurance—they cashed in on the Wall Street Farm Bill. They bought up their struggling neighbors’ land. They got wealthy while others were pushed out. This is a story of winners and losers by policy design.

The winners, what we define as those with more than $1,000,000 in sales each year, we call “Monopoly Farmers."1 That’s because these wealthy farmers are aligned with the likes of Cargill, Smithfield, ADM, Tyson, JBS, Bunge, Seaboard, Foster Farms, and more. Their interests are tax cuts for the rich rather than making sure meatpacking plant workers makes a fair wage. They’d rather worry about a loophole-riddled estate tax than think about how much they are overfertilizing their crops and poisoning the local water supply (plus, causing enormous climate pollution).

Much public policy discussion within agriculture rightfully focuses on the outsized market power of the largest seed companies, meatpackers, grain traders, and grocers. Farmers like to call for cracking down on concentration and consolidation in these sectors. However, its often said that big likes to work with big, and few are talking about the outsized political power of Monopoly Farmers.

Recent Agriculture Census data shows that agriculture has shifted tremendously since the 1996 Farm Bill. Fewer farms. Less farmland. Larger farms. More government spending to prop up the tri-headed monster of monoculture row crops, expanded production for biofuels, and a headlong commitment to providing cheap feed for industrial livestock factories.

Monopoly Farmers By the Numbers.

The 2022 Ag Census was released February 13th, 2024. The Ag Census is conducted every five years, and is a treasure trove of information about the size, shape, scale, and scope of farming and agriculture in the U.S. Farmers fill out detailed census forms that tabulate production practices, acres in production, markets, inventory of livestock, and more. The Ag Census plays an essential role in informing policymakers, the media, farmers themselves, business interests, and the general public about the state of affairs with respect to U.S. agriculture.

Since the implementation of the Wall Street Farm Bill passed in 1996, Ag Census data demonstrates the clear trend of fewer farmers, larger farms, and a decrease in farmland.

The following table documents the change in number of operations producing certain agricultural products. The number of producers involved with each sector of agricultural production decreased substantially since the Wall Street Farm Bill was pass. Two exceptions are poultry and egg production and vegetables for harvest, both of which have likely experienced large increases in operation numbers to due to the boom in local food markets, farmers markets, food hubs, and institutions purchasing locally-raised products

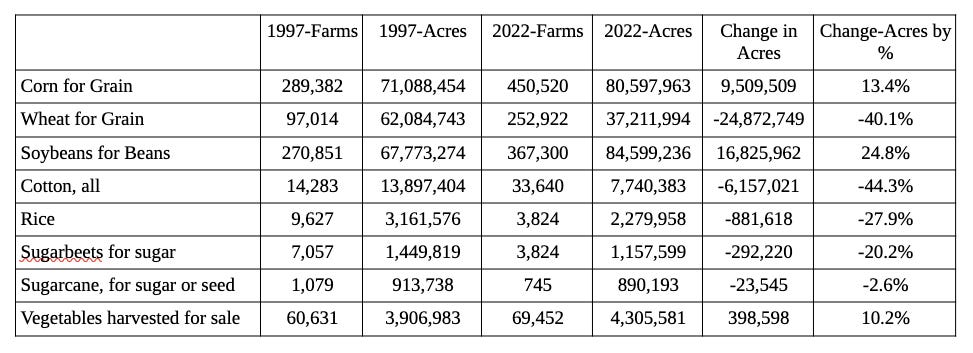

The following table documents the change in acres produced since passage of the Wall Street Farm Bill. Most rowcrops saw decreases. Corn and soybeans were the exception, as farmers chose to plow up pasture and conservation land and shift more acres to corn and soy from other crop such as wheat. Vegetable acres, as previously noted, also increased.

The Market Power of Monopoly Farmers.

The following table documents the current market power of the largest farmers compared to the production of the vast, vast majority of other farms. By “Market Value of Agriculture Products Sold,” Census data shows that only 5.5% (105,384 farms nationwide) of farm operations controls 78.3% of agriculture’s market value output. A smaller number of farms with more than $5 million in sales, 0.8% of farms (a mere 16,038 farms nationwide), controls 42.1% of market value.

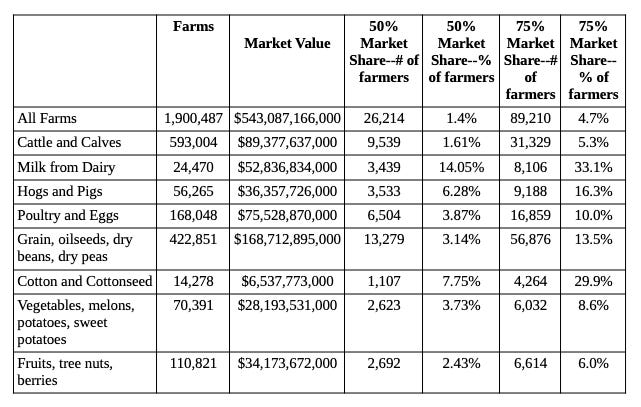

The following table provides Census data that documents market power by the largest farmers within certain commodities and sectors of agricultural production. Statistics are provided by number of farmers and percentage of farmers providing 50% and 75% of commodity market value by agricultural product sold.

Monopoly Farmers and the House Republican Draft.

At the core of Thompson’s farm bill is an increase in reference prices for commodity program crops. Reference prices are used to trigger payments to farmers who raise crops like corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, sugarcane, sugarbeets, and more. Thompson’s reference price increase is expected to cost $50 billion over the next decade. While improving the farm programs is certainly important, and a policy goal we share, the details of commodity payment reform are what matters.

The Republican approach to raising reference prices is expected to benefit a very small number of giant row-crop producers, the bulk of benefits accruing to fewer than 6,000 farms nationwide according to an analysis from the Environmental Working Group (EWG). EWG found that raising reference prices would help only 0.3% of the nation’s nearly 2 millions farms, mostly large peanut, cotton, and rice operations in Southern states. Predictably, a large number of Thompson’s political donations come from large commodity producers and organizations where these crops are grown.

The Farm Bill Debate Moving Forward.

The biggest challenge to passing a Farm Bill remains a bipartisan budget deal that caps federal farm and food spending. That cap creates a zero-sum political stand-off off between agribusiness and their Monopoly Farmers versus everyone else: the poor and working class, those fighting climate change, struggling rural communities, and millions of farmers who aren’t Monopoly Farmers. It is impossible to fully understand the debate around the farm bill without understanding what the Agribusiness and Monopoly Farmer lobbyists are fighting for and how much power they have in Washington D.C.

We understand that defining “Monopoly Farmers” by $1 million or more in agricultural sales is imperfect. We personally know numerous farm bill reformers, leaders who stand up against corporate agribusiness, committed conservationists, and scaled-up produce growers who oppose the agribusiness-friendly Farm Bill status quo. Our definition of Monopoly Farmer includes not only size and market power, but also the policy perspective of fencerow-to-fencerow crop production, defending factory livestock operations, deregulation, lower taxes for the wealthy, and ignoring corporate agribusiness control over markets.

The Cocklebur covers rural policy and politics from a progressive point-of-view. Our work focuses on a tangled rural political reality of dishonest debate, economic and racial disparities, corporate power over our democracy, and disinformation peddled by conservative media outlets. We aim to use facts, data, and science to inform our point-of-view. We wear our complicated love/WTF relationship with rural America on our sleeve.

Your chart on number of operations appears to be repeated at the spot where you meant to place acres produced. Am I incorrect?